Early Childhood Education Leadership in Times of Crisis. International Studies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

edited by Elina Fonsén, Raisa Ahtiainen, Kirsi-Marja Heikkinen, Lauri Heikonen, Petra Strehmel and Emanuel Tamir

About the book

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically affected all aspects of professional and private life worldwide, including the field of early childhood education and care (ECE). This volume sheds light on leadership in ECE: How did leaders experience the challenges they were facing and what coping strategies did they apply in order to deal with the changes in everyday life and practices in ECE centres? Authors from twelve countries present empirical findings gaining information on different crisis management mechanisms in ECE systems around the world.

Reading sample from pp. 15-21

Pedagogical Leadership in Early Childhood Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Finland

by Taija Korhonen, Elina Fonsén & Raisa Ahtiainen

Abstract

The daily life of early childhood education and care (ECE) in Finland changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020. The pandemic has had a significant impact on society at many levels, and it also has affected the work and workload of ECE leaders and the realisation of leadership. The aim of this research was to investigate ECE leadersʼ views on pedagogical leadership from the perspective of opportunities and challenges during exceptional times. The research uses the conceptualisation of broad-based pedagogical leadership as an analytical framework. The data consisted of the responses of ECE leaders (n = 492) to an electronic survey conducted in February 2021. There were several sections in the questionnaire, and in our research, we focused on two open questions concerning pedagogical leadership. In their responses, ECE leaders dealt with contrasting experiences of exceptional time leadership. Some leaders perceived that there was more time for pedagogical leadership than before; some felt the opposite. The widespread use of digital devices and programs that allowed distance working, meetings, and education brought significant changes to ECE. The success of strategic pedagogical leadership contributed to the development of practices and pedagogy; distance education was developed in many centres. The leaders highlighted the importance of leading the staff to ensure their wellbeing, professional competence, and capacity building.

Keywords: early childhood education, pedagogical leadership, broad-based pedagogical leadership, COVID-19

Introduction

The education sector experienced a new situation around the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The effects of the pandemic on education have been studied from many perspectives while researchers have tried to understand the phenomenon (e.g., Beauchamp et al. 2021; Lindblad et al. 2021). Several studies have shown the significance of communication and atmosphere to a solid and functional educational organisation (Ahtiainen et al. in press; Beauchamp et al. 2021; Hargreaves and Fullan 2020). Research at the beginning of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom claims that external factors, national structures, mandates, support, and advice affected the responsiveness of leaders, as well as subsequent management changes (Beauchamp et al. 2021). Hyvärinen and Vos (2015) identified creative thinking, problem-solving, and improvisation as critical elements of crisis management. In the event of a crisis, leaders try to maintain the coherence of a working community and to respond in a timely manner, according to changing situations. Moreover, researchers have highlighted the importance of trust and a positive atmosphere as fundamental structures of an educational organisation in a sustainable culture, even in times of crisis. In exceptional situations, an organisation must be stable to withstand external pressures (Ahlström et al. 2020). In addition, Fogarty (2020) drew our attention to distinctive categories of the four pillars of pedagogy in early childhood education and care (ECE): reassuring relationships, clear communication, continuous curiosity, and enabling environment. That is, the studies highlighted the aspects of a working community that are based on a confidential atmosphere and a robust shared vision formed through discussions.

In the Finnish context, the Act on Early Childhood Education and Care (540/2018) defines ECE as a goal-oriented entity formed through education, teaching, and care, emphasising pedagogy. In Finland providing ECE predominantly is the responsibility of its 309 municipalities, which must organise ECE according to the legislation and normative guidelines. Private service providers of ECE also follow the same legislation and guidelines as municipal ECE. In the work of the ECE leader, the essential element is pedagogical leadership. Educational changes in ECE require the realisation of solid pedagogical leadership. Finnish ECE leaders understand the importance of the curriculum as an instructor and developer of pedagogy and practices (Ahtiainen, Fonsén and Kiuru 2021). Also, the leadership of the educational plan process requires knowledge and understanding of the reforms and related expectations (Ahtiainen 2017).

During the past ten years, the Finnish ECE has encountered many changes before the ones caused by COVID-19, which again changed the course of work by introducing several new guidelines and instructions for the organisation of activities, that were continuously updated at various phases of the pandemic. ECE leaders were leading their centres while simultaneously updating instructions and informing staff and guardians about the changes. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic brought a new element to pedagogical leadership that broadly influenced the everyday life and leadership of ECE. With COVID-19, pedagogical solutions and everyday practices had to be changed. Further, ECE leaders had to consider how ECE could be organised in exceptional circumstances, and all work had to be undertaken without an existing operating model. At that point, some ECE centres had not yet established evaluation practices for their services (see Ahtiainen, Fonsén and Kiuru 2021). Gillberg and Ruokonen (2022) argue that the impact exceptional times have had on the daily practices in ECE has varied between the municipalities regarding the actual changes, decisions, and guidelines given by the local administration and in turn, that has affected the realisation of ECE during the pandemic.

This research investigated ECE leadersʼ views on pedagogical leadership opportunities and challenges during exceptional times. The conceptualisation of broad-based pedagogical leadership was used as an analysis framework (e.g., Lahtero et al. 2021).

Pedagogical leadership in ECE

The leadership of an ECE institution should be viewed through the basic mission of that field. Male and Palaiologou (2015) who highlight that the leadership of an educational institution should be viewed through practices and not through management theories. This is important because when we look at leadership practices, we note teaching, learning and outcomes, the expression of teaching, community ecology, and social relations within the educational organisation and the integration between them with each other. The social realities and educational outcomes in the educational environment are interconnected (Male and Palaiologou 2015).

The ECE Act (540/2018) emphasises pedagogy as one of the key responsibilities related to ECE leadership. Hjelt and Karila (2021) have studied the tensions related to the leadership in ECE and pointed out struggles between increasing efficiency and pedagogical quality demands. However, several studies have shown that pedagogical leadership affects the quality of teaching and pedagogy and through these, to the learning and well-being of children (Cheung et al. 2019; Fonsén et al. 2020; Strehmel 2016). It shows that pedagogical leadership is needed and leaders themselves have mentioned pedagogical leadership and human resource management as the most important in their work (Hujala and Eskelinen 2013).

Processes of pedagogical leadership are carried out following the ideology of shared leadership in educational organisations (Akselin 2013). Halttunen, Waniganayake and Heikka (2019) found that ECE teachers recognise their pedagogical responsibilities and support the professional competence of other team members. Previous studies (Heikka, Halttunen and Waniganayake 2018; Waniganayake, Rodd and Gibbs 2015) have also shown that leaders should clarify team membersʼ responsibilities and provide professional development courses for teachers to strengthen the realisation of pedagogical leadership in team leading.

Pedagogical leadership is formed in the interaction between the ECE leader and the staff. Research has shown that the leaderʼs assessment of his/her competence affects the assessment of staff and children (Soukainen 2019). Fonsén (2013; 2014) argues that successful pedagogical leadership is based on four dimensions of pedagogical leadership: context, organisational culture, professionalism, and management of the pedagogical content knowledge. In addition to these four dimensions, the value dimension affects all of them and is most relevant in successful pedagogical leadership (Fonsén 2013; Fonsén 2014, Fonsén and Lahtero in press). The concept of pedagogical leadership remains unclear to many leaders. Fonsén et al. (2022) have noted how many leaders have deficiencies in structuring their competency needs (Fonsén et al. 2022), and pedagogical leadership has become challenging when the leader has a multi-centre to lead and broad responsibilities.

Broad-based pedagogical leadership in ECE

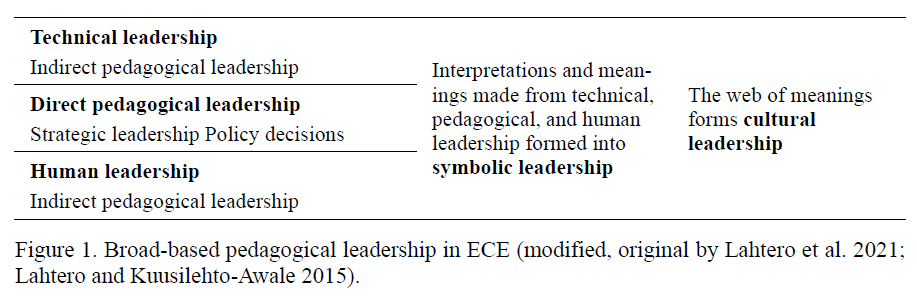

The job description and responsibilities of education leaders are multifaceted. They plan structures to support learning, facilitate teaching, and lead teachersʼ professional development. Leaders also support and help teachers in decisionmaking, learning, and mental growth (Raasumaa 2010). A broad-based pedagogical leadership framework defines these leading positions as indirect and direct pedagogical leadership, the implementation of which affects the symbolic and cultural meanings given to leadership (Fonsén and Lahtero in press; Lahtero et al. 2021; Lahtero and Laasonen 2021; Lahtero and Kuusilehto-Awale 2015). Figure 1 shows direct pedagogical leadership and indirect technical and human leadership, as well as symbolic and cultural dimensions to be equally relevant and influence each other.

The concept of direct pedagogical leadership (Figure 1) focuses directly on leading the learning and teaching context and related processes such as curriculum development and goal setting. These include setting shared objectives and the strategic leadership associated with them, maintaining a pedagogical discourse, and pedagogical alignments for the whole educational institution (Fonsén and Lahtero in press; Lahtero and Laasonen 2021; Lahtero and Kuusilehto-Awale 2015). In ECE, significant areas of direct pedagogical leadership, leading childrenʼs learning processes realisation by guiding staff include (1) pedagogical discussions and alignments in individual teams and in the community and, 2) shared and agreed guidelines, and (3) strategic management of the previous ones. The common guidelines and procedures call for a shared discussion on values, agreement on pedagogical guidelines and evaluation, and the development of a working culture based on them. (See also Lahtero and Kuusilehto-Awale 2015). Akselin (2013) sees that the objective of strategic leadership is to increase the quality of ECE by supporting symbolic tasks. Symbolic leadership aims to strengthen the community through shared views.

Indirect pedagogical leadership (Figure 1) is directed at the environment and context in which the process of learning and teaching occurs. These include leadership through technical structures and human resources. Technical leadership guarantees the implementation of the requirements, structures and strategies demanded and supported (Fonsén and Lahtero in press; Lahtero and Laasonen 2021). Leadership tasks include administrative decisions and routines, scheduling, and strategic financial resourcing (Lahtero and Kuusilehto-Awale 2015). Technical leadership is a fundamental requirement for the day-to-day process of an educational organisation. Functionally planned, organised, coordinated, and scheduled structures support the work communityʼs awareness of the tasks and objectives of each person (Fonsén and Lahtero in press, citing Sergiovanni, 2006). In ECE, the day-to-day structure leadership cover (1) planning shifts and meeting procedures, 2) strategic resourcing and budgeting, (3) administrative decisions and related routines, and 4) making annual plans and action plans. Leadership through technical structures ensures the adequacy of resources and budget for direct and indirect areas of pedagogical leadership.

Leading human resources is another dimension of indirect pedagogical leadership. It manifests the attention to staff needs, motivation and well-being. Leading human resources is typically related to leading the competence and capacity building of the staff and interacting with and supporting them (Fonsén and Lahtero in press). Human resources leadership in ECE, the psychological aspects, needs and motivation of staff, includes 1) leadership of competence and capabilities, 2) leadership of interaction, 3) supporting staff, and 4) the presence of a leader in the centre. The staffʼs professional competence and the capacity-building development requires motivation and a sense of professional empowerment. The leaders support staff through discussions, by providing a role model, that is, the leader influences the culture of interaction within the working community (Lahtero and Kuusilehto-Awale 2015). Successful leadership of competence and capacity building is possible when the leader succeeds in self-management (Raasumaa 2010). Further, a broad-based pedagogical leadership framework emphasises the competence of leadership and building capacity (Lahtero et al. 2021).

In the leadership of an education community, symbolic and cultural leadership (Figure 1) enable staff to achieve engagement and implementation (Fonsén and Lahtero in press). To understand the actions and symbolic meanings of the leader, one must see the reasoning behind the leaderʼs actions. With their actions and choices, the leaders model the meanings and values central to the working community (Lahtero and Kuusilehto-Awale 2015). Symbolic leadership can be seen in all dimensions of leadership. More critical than happenings in the organisation are the meanings and interpretations of the leaderʼs activities perceived by the staff (Lahtero 2011). Moreover, with symbolic leadership the leader builds trust, engages staff, and allows changing behaviour (Fonsén and Lahtero in press). Cultural leadership contains all the networks of meanings that the members of staff attribute to the leaderʼs actions. Essential tasks of cultural leadership include influencing the structure of reality and clarifying the more profound meanings of the work. When staff participate, interpret, and give meanings to the leaderʼs activities, all dimensions of a broad-based pedagogical leadership become visible in the process (Lahtero et al. 2021). The change is possible if the leader allows the staff to use their creativity and knowledge to find new solutions. The connection between all the broad-based pedagogical leadership dimensions is essential; when the leader considers all the dimensions, he/she can be called a highly qualified leader and the organisation is well-led (Fonsén and Lahtero in press).

Methodology

The purpose of this research was to examine the views of Finnish ECE leaders on the opportunities, challenges, and meanings of pedagogical leadership during the exceptional times of spring 2020. We looked at the topic through two questions.

First, we asked how Finnish ECE leaders described the meanings of pedagogical leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. And then further looked at the opportunities and challenges that could be identified in relation to the framework of broad-based pedagogical leadership?

The data were collected in February 2021 as a part of a research project on the COVID-19 pandemic and ECE (Nurhonen, Chydenius and Lipponen 2021). The survey was sent to the local ECE administrations in 146 municipalities. It was forwarded to leaders working in public and private ECE centres. In total, 679 leaders representing 120 municipalities responded to the survey. Respondents were from public (n = 433) and private (n = 59) ECE centres. In this research, we focused on written responses to an open-ended question concerning pedagogical leadership: What effects have the coronavirus-related exceptional circumstances had on pedagogical leadership? Please respond about the following resulting from the exceptional circumstances a) opportunities and b) challenges. Of the respondents, 72% (n = 492) answered at least one of these (a or b).

This research was based on a qualitative approach and theory-based content analysis method. The analysis was conducted deductively using the broad-based pedagogical leadership research framework. Qualitative content analysis is a systematic process of coding (Assarroudi et. al. 2018). In theory-based analysis, the data are coded according to the definitions of concepts in scientific theory (Potter and Levine‐Donnerstein 1999). Data management and analysis were undertaken using Atlas.ti 9 (2021). The first step was to classify the data set according to the broad-based pedagogical leadership framework. In the second and third rounds, we constructed more specific classifications of dimension contents.

***

Would you like to read more?

You can purchase the book or download the e-book in our shop:

edited by Elina Fonsén, Raisa Ahtiainen, Kirsi-Marja Heikkinen, Lauri Heikonen, Petra Strehmel and Emanuel Tamir