The City. An Interdisciplinary Introduction to Urban Studies

by Uwe Prell

About the book

“The City” resents the current state of urban research across various disciplines. The author offers insights into the views of those key disciplines that deal with urbanism, such as sociology, geography, spatial and urban planning, history, philosophy, and political science. He also takes language philosophy into account and shows the different meanings of concepts related to cities in a dozen word languages. An overview of central approaches and theories as well as of their practical application enables readers to see a familiar topic in a new light.

Reading sample from pp. 17-22

III. THEORY

A. The science of the city

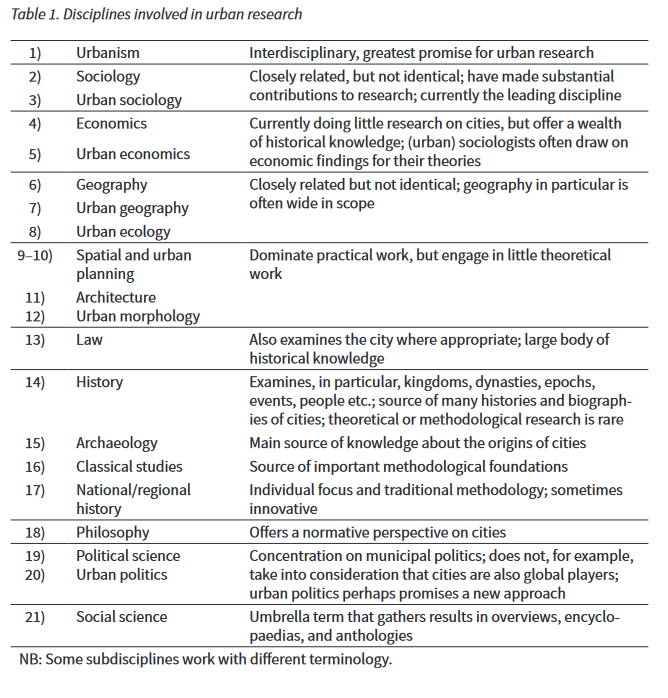

If something needs to be calculated, we turn to mathematics, when there is a structure to build, engineering provides the answers, and medicine knows best in case of illness. But who is responsible for cities? The rather unhelpful answer is: everyone and no one. Cities are so complex that one discipline can at best focus on one particular aspect. More than a dozen disciplines contribute to our understanding, and the overview in Table 1 is far from complete.

Despite their differences, all the academic fields agree that it is only possible to understand the city using an interdisciplinary approach. Yet despite this consensus, it has proven almost impossible to put interdisciplinary research into practice. Who would dare claim to have an overview of more than 20 disciplines?

For an initial exploration of the subject, it is therefore most useful to look at the encyclopaedias and introductory volumes that the individual disciplines have produced.

1. The big picture (urbanism)

Urbanism perhaps offers the greatest promise for research on the city. It is the

only field that is decidedly interdisciplinary in focus and – not to be underestimated – works with one of the strongest concepts, that is “urbanitas”. The Latin term originally designated a style that was perspicacious, elegant, and witty.

This connotation still exists in the many fashion labels, furniture designers, real

estate portals etc. that have “urban” in their company name. The use of the concept in modern science dates back to the Catalonian city planner Ildefons Cerdà. After the city walls of Barcelona were torn down, he sought a new approach to city planning and, finding no reference work, wrote one himself. His General Theory of Urbanization, published in 1867, was concerned with designing cities to promote social life.[4] That was his recipe for contemporary urbanity. Cerdà’s was the first work in which the term appeared in modernity. To this day, the term is usually used sociologically and descriptively or normatively and aesthetically. It is easy to trace the various debates as urbanism has evolved as a subject. In research done in the 1970s, to name just one example, the term “planning” was ubiquitous, today it is rarely used. Contemporary debates are less prone to generalizations; their scope is broader, and they are more willing to reflect on

newer methods.

At the same time, the term “urbanism” is used programmatically, for example to draw together urban management demands (“new urbanism”) or, since

the late 1980s, as a backlash against “urban sprawl”. Because the terminology is so broad, it can be interpreted in many ways. That is its strength – and its weakness. There is no clear analytical definition of urbanism. Nevertheless, there is consensus that urbanism integrates varying disciplines and approaches, without being an umbrella term. “Urbanism”, as one of the key books on the subject contests, “like no comparable term, comprises both a fundamentally interdisciplinary perspective and brings together all the various levels involved in urban development: analysis, planning and design,

steering, and critical reflection on what has been achieved”.[5] “Nothing,” writes the sociologist Peter Noller, “is united under this term. For that one would need a concrete question, a programme, or a scientific concept. … Urbanism holds together that which constitutes urbanity”. And, in fact, urbanism has yet to develop its own method or even theory.

Structural thinking predominates, built on traditional hierarchical models as in other disciplines. This concept is one of the greatest problems in urban research. It divides the world into levels, distinguishing between global, international, national, regional, and local. The city forms the final level. This view has serious flaws, for it fails to convincingly take our globalized present into account and can hardly explain phenomena such as the global city. This is not the only example in which basic concepts in the field are underdefined. What does urbanism add to our understanding of the city? It has strong terms and its aspirations are big enough to do the city justice. However, it has yet to develop a clear profile. For the time being it is a promise that is connected to the hope that “it will be better able to prevail as an academic discipline within the next one hundred years”. As yet, the discipline does not have the prerogative of interpretation when it comes to the issue – that is the purview of sociology and urban sociology.

2. City as society (sociology and urban sociology)

No other discipline has looked so extensively and so intensively at the city as sociology. The discipline’s founders, Max Weber, Ferdinand Tönnies, and Georg Simmel, contributed influential ideas, some of which we will look at more closely in the next chapter.[6] Many works from the early days of sociology remain notable today, especially those out of the Chicago School, the most influential school on interpreting urban life.

Important members of the Chicago School include Robert Ezra Park, Ernes Burgess, and Lewis Wirth. Inspired by Weber and Simmel, under whom he had studied in Berlin in 1899–90, Park founded the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago in the 1920s that went on to become the home of seminal works in microsociology and minority and poverty studies. The school produced a canon of urban research that was wedded to reality, had a sense of mission, and a desire to reach a broad public. At the same time, its works exhibited a “disconnection from and indifference to the physical city”.[7] For the Chicago School, the city was a social experiment or laboratory. And, in truth, the vitality of the work that came out of it should not distract from the fact that its perspective is very mechanical and formal. It aims at social engineering, and urban planning is its tool.

Thus, the Chicago School can be seen as a counterpart to another key position, epitomized by Jane Jacobs’s book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs called for the city to be seen as more than just a functional system, advocating, as Richard Sennett wrote, “for mixed neighbourhoods, for informal street life and for local control” in lieu of large-scale master plans. This created two opposing positions: for one thing, there is Jacobs’s rejection of the large-scale designs of Ildefons Cerdà (Barcelona), Georges-Eugène Baron Haussmann (Paris), or even Frederick Law Olmstedt (New York) or the influential Athens Charter. Second, she thus attacks one of the other leading leftist urban researchers, that is Lewis Mumford. Mumford was sceptical of Jacobs’s position and countered “in the name of socialism”, as Sennett relates, “that to fight capitalist top-down power, you need a sweeping countervailing force”. It is already clear that sociological positions are intertwined with city planning and architecture.

Of sociology and urban sociology it can be said that the work of the first two generations in particular remain benchmarks when it comes to the state of research. Building on them, three lines of research gained traction in the second half of the 20th century:[8]

- From the 1960s and 1970s, leftist research increasingly developed (spatial) sociological theories that were given significant impetus through the works of Henri Lefebvre. A direct line can be drawn from there to Manuel Castells’s Space of Flows. These researchers interpreted the city as a social space, with the aim of righting the flaws they found – for example unequal opportunities – by restructuring or redistributing space. Dieter Hoffmann-Axthelm, a radical protagonist of this faction, propagates a fundamental reassessment and redistribution of urban space, and in the end a recreation of the city.

- A second line of development took place in the area of post-war urban planning and, from the 1990s, the political and spatial realignment of CentralEurope. The subdiscipline urban sociology grew out of this discussion. The work of Hartmut Häußermann is exemplary for this faction, as its covers the entire spectrum of this topic.

- But the undoubtedly most important development was in relation to globalization, and increasingly also the digital transformation within and through cities. What was key in this debate was Saskia Sassen’s seminal work The Global City. Sassen recognized this type of city as the main driver of globalization. Her thesis amounted to no less than a completely new assessment of the role of the city in international relations. The importance of her ideas and the paradigm shift she initiated is only gradually becoming clear.

The first and third positions in particular point towards a core problem of urbansociological research: the delineation of “city” and “society”. Society is perhaps the most important category in sociology. Its roots reach back to Aristotle’s view of people as zóon politikón, creatures whose nature it is to live in society. The term became popular during the Enlightenment, and the emerging middle class used it to underline their self-understanding as a “citizen” society – as opposed to, for example, a feudal state.

The concept of society has always been connected to ideas of space, and the state became the main conceptual figure in modernity. Society is a hierarchical concept, it is the main category under which institutions such as state, family, law, or education form subcategories. The city can also be placed within this hierarchy, and as long as the boundaries are clear, this model makes sense. This is particularly true for the 19th and 20th centuries, a phase in which states were strong and there was no need to draw a distinction between the state and society. Today, however, other phenomena have taken centre stage, such as global financial flows, the digital transformation, or new forms of living together. These cannot be clearly delineated using traditional terminology. While categories such as family, state, and society still hold meaning, their content is shifting and they are insufficient when it comes to explaining contemporary forms of living. Just as the city can no longer be seen as a subcategory of the state, neither can it be regarded as a subcategory of society. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that many authors see the city mostly as the stage on which societal conflicts play out. For them, there is no need to draw a distinction between “social society” and “urban society”. The most radical proponent of this viewpoint is the sociologist Jürgen Friedrichs, whom we will look at briefly in III.B.6. He is vehemently against any such division.[9] And so placing the city in context remains a major challenge of sociological urban research. There is, currently, no one prevailing opinion. Recent work on the sociology of space aims at providing an understanding of the delimitation and dynamization of space. It thus has similarities with the concept of governance in political science that seeks to expand the boundaries of the classic definition of politics and to establish a new understanding. Other authors propose speaking only of a lower or higher density of spatial structures.

At such an abstract level, it is impossible to contradict one or other position. Nevertheless, the conclusion remains unsatisfactory. Reducing city, state, and society to spatial structures that need only be described and calculated is unconvincing. Taken to the extreme, it would mean that the city is no more than a form in which humans live mostly dependent on spatial structures – a very one-dimensional view of people and their world. This harks back to an old debate that goes well beyond sociology and into the fields of ethnology and philosophy. It is controversial whether structures or conditions influence human beings or vice versa. There is no meaningful way to answer such a generalized question. Since the influences are reciprocal, satisfying answers can only be given in concrete cases.

The complexity of the questions reveal the very broad scope and diversity of sociological approaches. It also reveals the many small but important differences within and between sociology and urban sociology. As close as they are, there are many key differences when one looks in detail at their understanding. For that reason, this discipline has not yet delivered a generally accepted analytical definition of the city. Instead, there are many often similar, and sometimes completely contradictory, definitions, as can be seen in the many encyclopaedias and handbooks. While contributions to encyclopaedia often list only a few key characteristics of cities, the number of features grew after urban sociology was established. Yet these criteria are almost never drawn together to form a definition. If there is consensus at all, it is that the terms size, density, and diversity are necessary but insufficient to any description of the city. Thus while none of the varying branches of sociology define the city, they have given us many well-founded contributions towards an understanding of the city.

One more thing should be noted: From the founders of the discipline to the present, sociologists have always made an effort to look beyond their own discipline. One of their greatest interests has always been in economics, a feeling that has so far not really been reciprocated.

[4]Sennett, Richard (2018), Building and Dwelling. Ethics for the City. New York, p. 37.

[5] All citations on this page are taken from: Frey, Oliver; Koch, Florian (eds.) (2011), II. Gesellschaft, Governance, Gestaltung, Vienna, Berlin. More specifically: Tilman Harlander, p. 17; Peter Noller, p. 15–16; Sibylla Zech, p. 14; Klaus R. Kunzmann, p. 19.

[6] Tönnies, Ferdinand (1887), Community and Civil Society, trans. by Jose Harris and Margaret Hollis. Cambridge, p. 26–27. Simmel, Georg (1984, original 1903), The Metropolis and Mental Life, in: Simmel, Georg (1984), On Individuality and Social Forms. Chicago, p. 324–339. Weber, May (1958, original 1922), The City, trans. by Gertrud Neuwirth. Glencoe.

[7] Sennett, Richard (2018), p. 69. A further quotation at the end of the next paragraph: ibid, p. 78.

[8] Castells, Manuel (1996–1998), The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. Oxford, Malden MA. Vol. 1 (1996), The Rise of the Network Society | Vol. 2 (1997), The Power of Identity | Vol. 3 (1998), End of Millennium. See also Sassen, Saskia (1991), The Global City. New York, London, Tokyo

[9] Friedrichs, Jürgen (1997), Stadtanalyse. Soziale und räumliche Organisation der Gesellschaft. Reinbek.

***

Would you like to read more?

Order via our webshop

The City. An Interdisciplinary Introduction to Urban Studies

by Uwe Prell