How can teachers and educational professionals handle challenging situations in schools? How can they manage the resulting conflicts? A reading sample from “Managing Challenging Behaviour in Schools. Educational Insights and Interventions” by Ulrike Becker. Read a snippet from the second chapter “Pupils with aggressive behaviour: Behaviour towards teachers”.

A German edition was published in 2023 under the title „Auffälliges Verhalten in der Schule. Pädagogisches Verstehen und Handeln“.

Reading sample “Managing Challenging Behaviour in Schools”

2. Pupils with aggressive behaviour: Behaviour towards teachers

2.1 Theoretical considerations

In schools and lessons, there are always educational situations in which teachers feel provoked or threatened by a pupil or group of pupils. Such situations usually lead to feelings of powerlessness, helplessness and feelings of powerlessness and helplessness among teachers. In rare individual cases, teachers may also be psychologically or physically harmed by young people.

This chapter deals with children and young people who display aggressive behaviour towards teachers due to impairments in their emotional or social development.

Children or young people can experience teachers as threatening in the classroom. They either feel they are being bullied and devalued by them or they are looking for more attention. It is not uncommon for pupils to oscillate between the two views. For example, a child may feel disadvantaged compared to other children because they are the last to receive a worksheet from the teacher. A child may also feel bullied because the teacher wants to talk to them during the break about the maths methods they have used to solve problems. A child may also feel disadvantaged if they are called on too often by the teacher in class and asked to speak or complain because this happens too rarely. Subjectively experienced discrimination, paternalism or disregard can therefore be causes that trigger aggressive behaviour towards teachers. This can manifest itself in insults, verbal abuse or the throwing of paper balls or objects at the teacher. Sometimes there are also verbal threats of violence or threats with weapons, such as a knife.

Due to the negative consequences for all parties involved, such situations should be prevented. Constructive solutions must be found in conflict situations. In terms of inclusive education, the aim must be to “limit violence instead of marginalising young people” (Auchter 1994, 55) [Translated by the author].

In order to deal with aggressive behaviour towards teachers in an educationally constructive way, a deeper understanding of difficult situations is necessary. The pupilʼs perception of the situation is the starting point of a conflict, and the aggressive behaviour is an unconscious cry for help from the child or young person to their social environment. Three questions will be pursued in the following:

What are the causes of aggressive behaviour in children and young people who have experienced too few supportive relationships in early childhood? What part do teachers play in difficult educational situations? How can prevention be strengthened through educational action and how can conflicts in the classroom be reduced?

Impairments in early childhood

For healthy emotional development, children need supportive relationships with parents. However, these attachment figures can also be replaced by other adult attachment figures who are permanently available to children when children grow up in adoptive or foster families, with grandparents or in shared flats. Continuous, supportive relationships in early childhood are referred to as primary relationships or attachment (Becker 1995a). Providing support implies the provision of nourishment, the availability of caregivers, protection from physical and emotional injury and the endurance of difficult situations with the child. The following section describes some typical family situations that affect the emotional-social development of children to such an extent that challenging behaviour can occur.

If parents are too preoccupied with their own material or psychological problems, alcohol addiction or drug use, they can only be available to the child as a carer to a limited extent or not at all. Young children then often develop early childhood attachment disorders, while older children often take over parental functions on behalf of their siblings.

When coping with difficult situations with an infant or toddler, problems can also arise if parents are insecure in their role as parents due to their own biographical experiences. It is possible that even loving parents may display behaviour in difficult situations that has a negative impact on a childʼs emotional development. For example, parents may shake a child if it cries for a long time. Such a situation can arise when parents lose their patience. These are primarily parents who are still unsure or overwhelmed in their role and experience helplessness in their relationship with their child.

This can lead to shaking trauma. Shaking trauma is the most common nonnatural cause of death in children (Nationales Zentrum frühe Hilfen, 2022). The number of unreported cases is unknown. Every year, between 100 and 200 children are hospitalised due to shaking trauma. 10 to 20 per cent survive this without consequential damage. 10 to 30 per cent die as a result. 50 to 70 per cent suffer lifelong consequences, such as visual and speech disorders, cognitive learning and developmental delays, seizures or even severe permanent physical and mental impairments (Nationales Zentrum frühe Hilfen 2022).

Children who experience too little emotional support within the primary relationship in their early childhood initially develop little or no ability to empathise with others (Winnicott 2023). They develop unconscious fears and feel powerless. This is why they repeatedly seek support from their primary carers.

If they are unsuccessful, they often defend themselves against their powerlessness and fear through aggressive behaviour. It is also possible for children to withdraw into themselves and show depressive symptoms.

If a parent or guardian is violent towards a child, children can also identify with the parent and behave violently towards others themselves. This makes them feel strong and reduces their fears.

If children with impaired emotional development experience their school as their home, they unconsciously project aspects of their primary caregivers onto teachers. As a result, they feel the powerlessness, fear or anger towards these adults that they have developed in their primary relationships. They may also steal objects that are meaningful to them or the teacher (Becker 1995a, Leber 1983, Gerspach/Katzenbach 1996, Hehn-Oldiges 2021, Katzenbach 2004, Würker 2007, Zimmermann/Würker 2023).

Such behaviour, which is perceived at school as challenging behaviour or an attack on others, represents a desperate cry for emotional support from the professional reference persons The well-known British child and adolescent psychiatrist and psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott (…) speaks of delinquency as a sign of hope (Auchter 1994, Becker 1995a, Winnicott 2023). Teachers cannot replace parents or guardians for children. However, they can provide support and boundaries, which favours childrenʼs ego integration and enables them to develop the ability to empathise with others. To this end, it is necessary for teachers not to intervene when children or adolescents become challenging and aggressive, but to offer them support (Leber 1983, Gerspach/Katzenbach 1996, Würker 2007, Hehn-Oldiges 2021).

The part of teachers in difficult situations

Teachersʼ behaviour is shaped by their own personality and biography. These unconscious parts of a teacherʼs personality come to the fore in the classroom, especially when pupils display challenging behaviour, provoke and push the teacher to their psychological limits.

The pupil unconsciously transfers aspects of their parentʼs personality to the teacher. This is referred to as transference. The pupilʼs behaviour triggers the teacherʼs unconscious reaction, which is also based on their biographical experiences. This is called counter-transference. The interplay between transference and countertransference in the classroom is referred to as a scene (Becker 1995a, Leber 1983, Gerspach/Katzenbach 1996, Würker 2007, Zimmermann/Würker 2023). Such unconsciously occurring scenes can be the trigger for the teacher to demand that a child or adolescent be segregated in a special institution because the situation at school seems hopeless. This is particularly the case if the teacher identifies with the powerlessness of a child due to their own biographical experiences. Teachers then often say: “I no longer know how to help the child. It would certainly be easier to do this in a youth welfare centre or a special school. The teachers there are trained to do that.”

This is usually a misjudgement: the teachers do not realise how successfully they are already supporting the pupils concerned in everyday school life. Be it by preparing differentiated work tasks for them, praising them, giving them a pencil or eraser if one is missing, providing drinks, seeking individual dialogue with them or taking them on class trips lasting several days.

For children and adolescents who have experienced too little emotional support in the primary relationship, it is initially very important that the teachers tolerate them despite their disruptive behaviour and do not break off the relationship by refusing to teach such a child and demanding that the child be segregated. The behaviour of children that affects teachers or other children must be limited without excluding the child in question (Auchter 1994, 55). This endurance can enable the child to develop the capacity for concern (Winnicott 2023). If a child achieves this competence in interaction with a teacher, this leads to feelings of guilt in the event of aggressive behaviour towards the teacher. The attainment of the capacity for concern becomes clear to teachers when a child or adolescent shows a tendency to make amends by wanting to repair or replace objects that they have broken or by bringing the teacher concerned a gift, drawing a picture for them or showing unexpected kindness in some other way. Developing the capacity for concern is one of the key prerequisites for reducing or eliminating aggressive behaviour in the long term.

Coping with children and young people who are experienced as difficult is of central importance for the development of pupils and at the same time a very rocky and long road for teachers. They need support in the form of teamwork, case counselling, supervision or coaching.

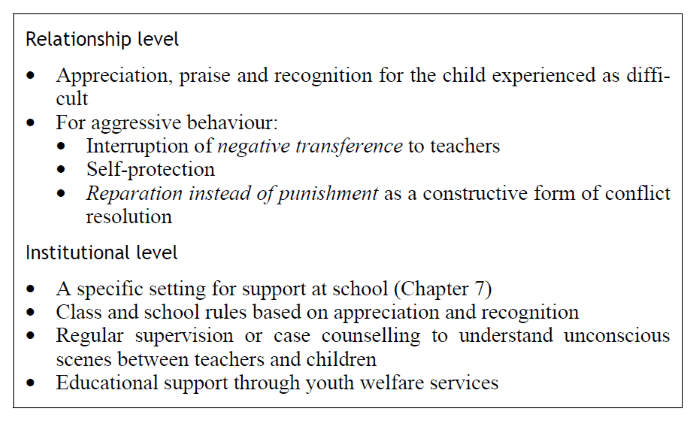

The success of inclusive education in the case of challenging behaviour requires supportive relationships and a setting within the school that allows the effect of supportive relationships to unfold. The following aspects at the institutional and relationship level are particularly important for implementation:

***

Would you like to continue reading?

Order “Managing Challenging Behaviour in Schools. Educational Insights and Interventions” in our shop or download as e-book

Managing Challenging Behaviour in Schools.

Educational Insights and Interventions

by Ulrike Becker

More reading samples can be found on our blog.