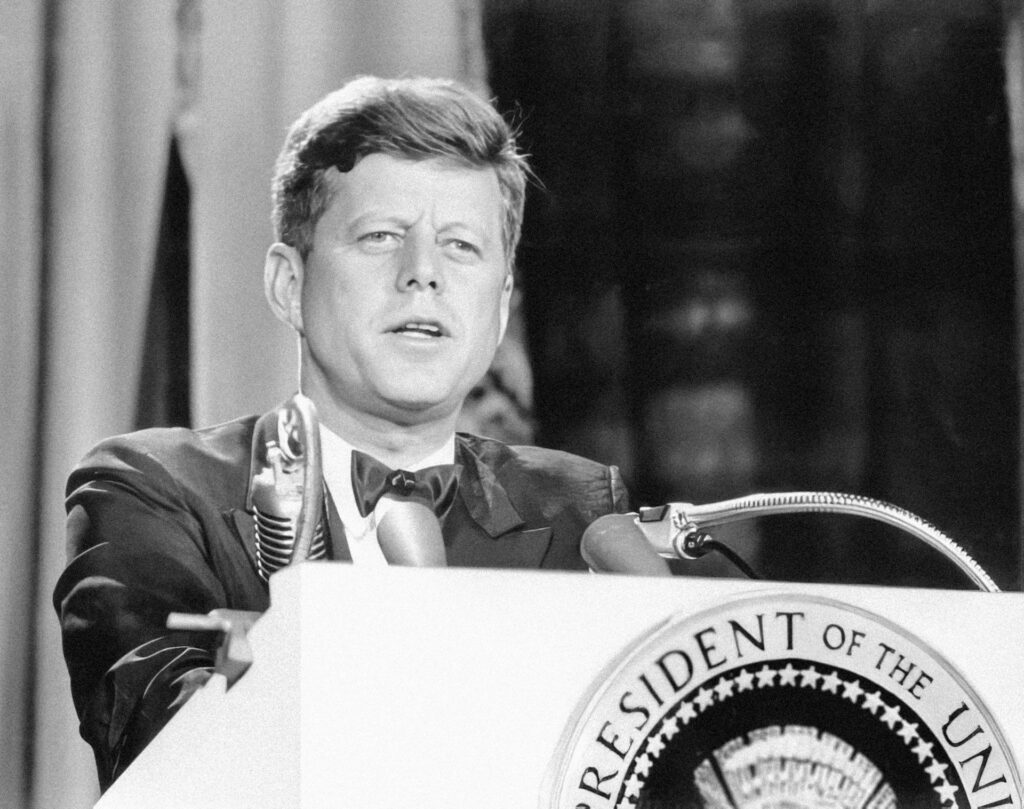

Civil Rights and Political Realignment: The Presidency of John F. Kennedy

Robert E. Gilbert

Northeastern University1

PCS – Politics, Culture and Socialization, Issue 2019-2020, pp. 18-50

Abstract: During his presidency, John F. Kennedy emerged as a powerful force for change in the area of equal rights for the nation’s black population. In addition to the major civil rights legislation that he proposed and that Congress ultimately enacted, Kennedy served as the nation’s teacher, trying to awaken in citizens a sense of understanding and fair-mindedness. He referred publicly to civil rights as a “national crisis of great dimensions,” and then worked hard in trying to resolve that crisis in a positive and peaceful way. However, the civil rights activities of both John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson contributed immeasurably to a powerful and enduring political realignment in the United States. Millions of Democrats, located heavily in the south, were highly disaffected by Kennedy’s and Johnson’s activism in civil rights. Many moved out of the Democratic Party and then into the Republican Party after flirting in 1968 with the short-lived and overtly racist American Independent Party. Today, more than fifty years later, the south remains strongly Republican.

Keywords: Civil rights, John F. Kennedy presidency, Southern United States, Republican Party

Introduction

As a member of the United States Congress for fourteen years, John F. Kennedy advanced a “nuanced strategy on civil rights” that aimed to end the more odious abuses of racial segregation while still appeasing the more traditional southern voters.2 However, shortly after taking the oath of office as President of the United States on January 20, 1961, Kennedy demonstrated a noticeably more active interest in civil rights progress. When, for example, he noticed that all of the Coast Guard cadets marching in his inaugural parade were white, Kennedy quickly issued an order to the Commanding Officer of the Coast Guard Academy, directing him to begin recruiting and enrolling black students without delay.3 This, then, was one of Kennedy’s first official acts as a new president. Soon he saw both black students and black faculty members recruited for the first time since the academy’s founding in 1876.

Kennedy’s interest in non-discrimination was almost certainly heightened by the fact that as an Irish-American school boy, he had been the victim of “ethnic, social and religious prejudice.”4 Later, his Irish heritage offended some of the power brokers and voters with whom he came into contact and anti-Catholic sentiment was a significant problem for him in winning the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination and then the general election that followed.5 As an example, Protestant evangelicals in September, 1960 issued a public denunciation of the Catholic candidate’s fitness for office.6 Kenneth W. Thompson has pointed out that, in the face of this attack, many observers predicted that Kennedy was doomed to defeat.7 Therefore, he had to respond vigorously in order to demonstrate to concerned Democratic Party leaders that “ his youth and Roman Catholicism had not ruined the party’s chances in the Fall election….”8

In mid-September, Kennedy delivered an address in Texas to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association during which he asserted that “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute – where no Catholic prelate would tell the President (should he be Catholic) how to act….”9 Kennedy’s victory margin over Republican Richard Nixon was only 119,000 popular votes (out of the 68.4 million votes cast), with surveys suggesting strongly that the factor of religion had played a clear role in narrowing the gap between the two major party nominees.10

As a new Chief Executive, Kennedy tried to exert quick but subtle influence over racial attitudes by the way he interacted personally with African Americans and responded personally toward the issue of racism. He danced with black women at the 1961 inaugural balls and invited more black guests to the White House than any president before him, socializing with them comfortably and with charm. Also, although Kennedy had considered appointing Senator William Fulbright of Arkansas to the position of Secretary of State, he ultimately rejected the idea because Fulbright had taken a “a segregationist stance in his Arkansas constituency.”11 Then, early in his term, the new President told the press that he “personally approved” of his brother’s resignation from a segregated club in Washington, D.C.12 His overt inclusiveness, then, helped foster stronger racial acceptance in some quarters of American society and, in effect, “represented a genuine paradigm shift in American racial politics.”13

Impactful Press Conferences

In addition to the subtle influences that he tried to exert over societal inclusiveness, John F. Kennedy was keenly aware of the power of television, then a relatively new medium of mass communication. He had been consulting with media experts and media executives since he started active national campaigning in 1957,14 trying to learn as much as possible about the potentialities of the medium. So it was not surprising that, early in his presidency, he announced that he would allow live television coverage of his press conferences. Since Kennedy was extremely well informed, highly articulate and thoroughly videogenic, he proved to be a master of television communication. He typically engaged in some 20 televised press conferences a year and his meetings with the press were designed to appeal to the American public while at the same time, satisfying the press corp’s interest in having direct access to the nation’s Chief Executive. More specifically, Kennedy’s 63 presidential press conferences, clearly designed to educate the people even more than the press,15 attracted large audiences and invariably won highly favorable ratings.

Kennedy’s first press conference, on an evening shortly after his Inauguration, was tuned in by a remarkable 65 million persons, and the President’s performance was flawless.16 Somewhat surprisingly, the Administration moved subsequent press conferences to daytime hours in order to avoid over-exposure. These daytime events typically attracted some 20 million viewers, a huge daytime audience. As a sign of Kennedy’s adeptness at interacting with the press in a question/answer format, the number of television sets in use every time he went on the air actually increased by some 10 percent.17 Beyond doubt, Kennedy’s meetings with the press drew huge audiences and provided him with a powerful nationwide pulpit. In other words, the President’s press conferences were watched by northeners, midwesterners, westeners, and viewers in the south – where resistence to his words about civil rights was undoubtedly more intense than elsewhere in the country.18

News coverage at the time focused heavily on racial discord and violence. Television regularly broadcast “ugly images of racist white mobs attacking black protesters in the United States, the so-called ‘land of the free.’”19 The number of questions touching directly or indirectly on aspects of civil rights that were directed to Kennedy at press conferences expanded greatly over the course of his presidency, from 10 in 1961 to 25 in the months of 1963 during which he was the nation’s leader. The manner in which the President answered those questions made his deep concern about the issue absolutely clear, so clear, in fact, that no opponent of civil rights could take comfort in the slightest ambivalence or equivocation on the part of the nation’s chief executive. Contrary to some other contemporary Presidents, Kennedy never used reporters’ questions as a vehicle for criticizing the courts or hinting disapproval of court decisions. Rather, he used them to serve as the nation’s teacher not just in equal rights but also in human decency.

1 Correspondence: r.gilbert@northeastern.edu

2 Christopher Sanford, Harold and Jack: The Remarkable Friendship of Prime Minister Macmillan and President Kennedy, Amherst, New York, Prometheus Books, 2014, p. 51.

3 Kenneth P. O’Donnell and David F. Powers, Johnny, We Hardley Knew Ye, Boston: Little Brown, 1970, p. 248.

4 Nigel Hamilton, JFK: Reckless Youth, New York: Random House, 1992, p. 206.

5 Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1960, New York: Atheneum Publishers, 1961, pp. 354-355.

6 Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy, The President’s Club, New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012, p. 255.

7 Kenneth W. Thompson, The President and the Public Philosophy, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981, p. 214.

8 Thomas E. Patterson, The Vanishing Voter, New York: Vintage Books, 2003, p. 116.

9 White, The Making of the President 1960, 1961, p. 391.

10 Gerald Blain and Lisa McCubbin, The Kennedy Detail, New York: Gallery Books, 2010, p. 33.

11 O’Donnell and Powers, Johnny We Hardly Knew Ye, 1970, p. 236.

12 Public Papers of the Presidents, John F. Kennedy, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1963, p. 358.

13 Nick Bryant, The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality, New York: Basic Books, 2006, p. 464.

15 Thomas Oliphant and Curtis Wilkie, The Road to Camelot, New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017, p. 295.

16 Theodore C. Sorenson, Kennedy, New York: Harper & Row, 1965, p. 322.

17 Harold Mendelsohn and Irving Crespi, Polls, Television and the New Politics¸ Scranton, Pennsylvania: Chandler Publishing Company, 1970, p. 274.

18 Robert MacNeil, The People Machine¸ New York: Harper and Row, 1968, p. 297.

19 Thomas E. Patterson, The Vanishing Voter, New York: Vintage Books, 2002, p. 35.

20 James L. Swanson, End of Days, New York: Harper Collins, 2013, p. 34.

* * *

Would you like to continue reading? This article was published in issue 2019-2020 of PCS – Politics, Culture and Socialization.

Would you like to continue reading? This article was published in issue 2019-2020 of PCS – Politics, Culture and Socialization.

More reading samples …

… can be found on our blog.

© Unsplash 2024 / image: Florida Memory